Harmonising the major scale- why do certain chords go together?

As a guitar, ukulele, music theory and composition teacher I am often asked “Why do these chords often go together but never those ones?” or “Why are so many songs mostly G, C and D?”.

In this blog I will attempt to demystify the reasons behind certain chords being in certain songs and explain the patterns so that you can write your own music more easily. You will also find this information very helpful when trying to work out songs by ear or add your own chords to a melody.

Let’s begin…

Firstly, let’s look at the major scale. The major scale is like the great-grandparent of all the other scales. A scale is a simple enough concept- it is a selection of notes which can be recognised by the gaps (or intervals) between them. So if you pick any note on a guitar, you will hear a major scale if you go up by the following steps:

Tone, Tone, Semi-tone, Tone, Tone, Tone, Semi-tone.

To hear this in action, pick an open string on your guitar and play a major scale on that string. A tone is a gap of 2 frets and a semi-tone is 1 fret. So for example if you wanted to play a G major scale you would pluck the open G string, then frets 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11 and finally 12. The 12th fret is an octave above the original note you played, aka G again. For physics buffs the frequency of this pitch is exactly double that of the starting pitch (you can find more information about this on my series of blogs about the physics of music, coming very soon- [popup_anything id=”794″] to be kept abreast of new posts).

If you pick any other position on your guitar and move up by the same series of gaps you will have a major scale of whichever note you started on, so if you play the open D string then frets 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11 and 12 you will have a D major scale. The notes are D, E, F#, G, A, B, C# and D.

Arnold Schoenberg, serialist composer

If a listener says “This tune is happy”, it probably is in a major key. If they say it is “sad”, “gloomy” or even “melancholic” they are probably saying it’s in a minor key. If the tune is written using a set of notes that is not a conventional scale many listeners will say “It doesn’t sound like music to me”. For examples of this look up the serialist work of composers like Arnold Schoenberg which deliberately uses a “method of composing with 12 tones that are related only to one another”, the gamelan music of Indonesia or more modern artists who use frequency modulation to achieve harmonious scales with inharmonic root notes (I particularly recommend Sevish).

Being in a key

When someone says that a piece of music is “in the key of D major”, what they mean is that the piece uses only the notes of the D major scale. No matter their order, if the tune contains only notes from this selection then it is still in the key of D major. Generally the key note will be the most common and will likely be the final note in the melody. Western popular music dictates that tunes should stick to one scale (or mode) fairly rigidly with occasional accidentals (altered notes) or modulations (key changes). Classical music, jazz etc make more use of modulation, aka changing key mid song or piece. On the other hand folk, pop and more mainstream genres tend to pick one mode or key and stick to it.

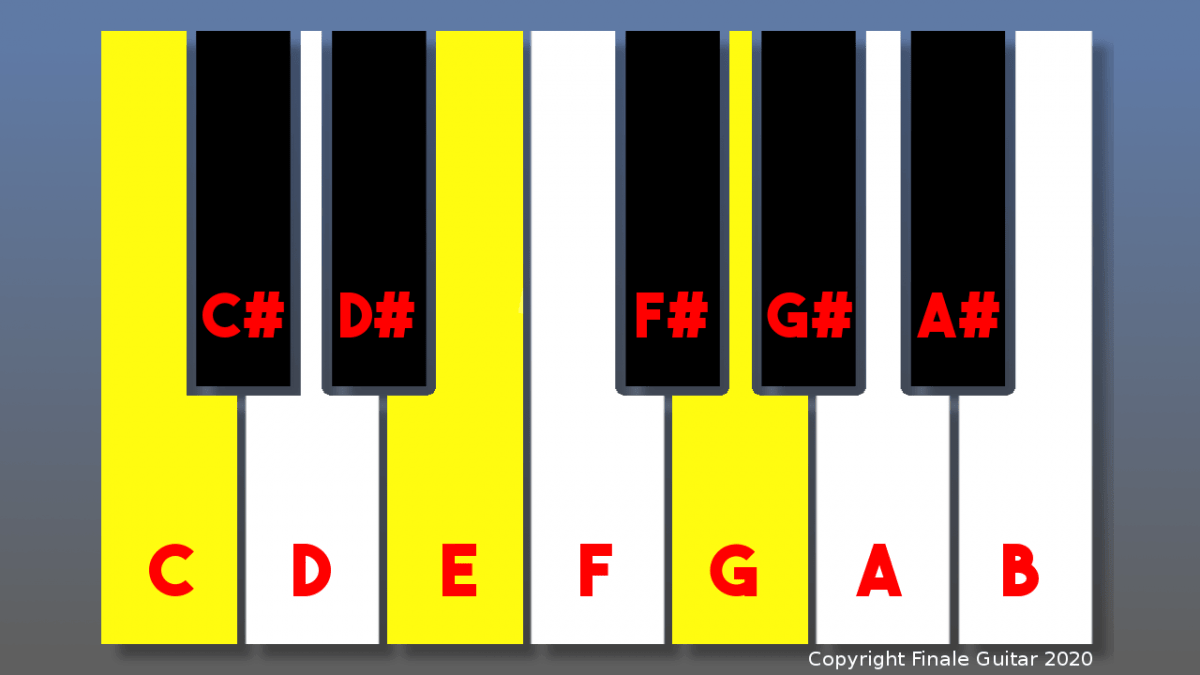

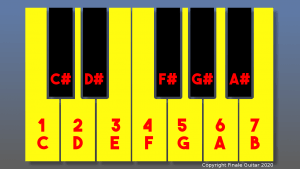

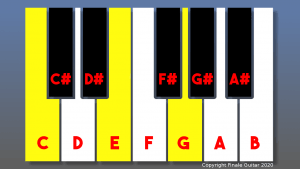

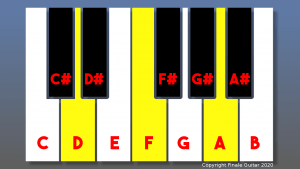

On the piano below you can see the notes of a C major scale. The white notes of a piano are arranged in the intervals of a major scale (tone, tone, semi-tone, tone, tone, tone, semi-tone) starting and ending on C. Consequently the scale of C major contains no sharps or flats. This is because C – D is a tone (two hops- skip over C#), D – E is another tone (skip over D#), E – F is a semitone (because there is no black note between E and F) etc etc. Notes used are all numbered and highlighted in yellow.

If you start and finish on G and go up by the same intervals you will hit F# on the way up, meaning that you would have to use those notes throughout the tune in order to be in the key of G major.

The sharps or flats in a given scale or key are called its key signature. All key signatures can be seen clearly on the circle of fifths:

This shows you which sharps or flats are in every major key. Note that, starting from C, for every one place you go to the right, you arrive at a key signature containing one more sharp than the previous one. For example C has no sharps, G has one, D two, A three and so on. Each position to the right is a fifth higher than the previous one. C – G for example is four positions further into the musical alphabet including the starting note- C, D, E, F, G . Likewise for G – D: G, A, B, C, D.

Notice too that the sharps are always added in the same order; F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E#. I like to remember this with the helpful mnemonic “Fat Cats Get Drunk After Eating Broccoli”.

Why do some keys have flats and some keys have sharps?

The above is a scale of F major. The 4th note in it could be referred to as A#. However, if we called it that, our scale would go “F, G, A, A#, C, D, E, F”. This would be very confusing as we’d have two As and no B. For this reason we refer to A# as B♭ in order to include every letter once. As you move left round the circle you are going down a fourth each time. This is the inversion of going up a fifth; F up to C is up a fifth and C down to F is down a fourth.

The flats are added in the following order:

B♭ , E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭ .

I remember these by making the noise that they spell out in my head. Making the noise “Fbeadg” makes me smile every time and for some reason I find this easier to remember than a mnemonic. That being said, on a recent scroll through the ABRSM forum I found the following fantastic pair of mnemonics for remembering the order in which sharps and flats are added:

Sharps: Father Christmas Gave Dad An Electric Blanket

Flats: Blanket Explodes And Dad Gets Cold Feet

The chord scale- which chords go in a major key

Once you know which notes will be in your song’s melody you need to know which chords might fit with them. The simplest chords are made of three notes in a pile and our called triads. They are made using the first, third and fifth degrees of a scale. More information on the physics and practicalities of chord construction will be coming up in future blog posts!

If our melody uses only the notes of a C major scale it follows that we can only use those notes to build our chords too. Thus there are seven triads to choose from, one for each note in the scale.

How triads work (simple chord construction)

- Two notes separated by a gap of four semi-tones produce a major third when played together (happy sounding) and a gap of three semi-tones make a minor third (sad sounding).

- A triad with a major third between its lower two pitches and a minor third stacked on top will be heard as a major chord.

- A triad with a minor third between its lower two pitches and a major third stacked on top will be heard as a major chord.

NB: A semi-tone is one fret on a guitar or any single key of either colour on a piano. A tone is two frets or keys.

So, if we make our first chord of C major by playing the first, third and fifth notes of the scale, you can see that we hit C, E and G.

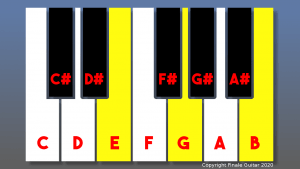

If we make a chord for the second note of the C major scale in the same way we get this:

This is a D minor chord, because there is a gap of 3 semi-tones between the first two notes and 4 between the second 2.

The third chord, beginning on the third note of the scale is this:

AKA E minor.

If we continue to do this for the rest of the scale we can conclude that a given scale will contain the following chords:

I Major, II Minor, III Minor, IV Major, V Major, VI Minor, VII diminished.

After this you are back where you started as the scale contains only 7 notes.

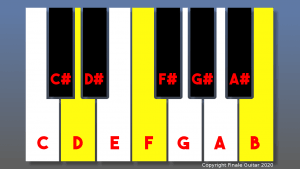

The VII chord is diminished because the gap between the first 2 notes in it is a minor third, aka 3 semi-tones and the second gap is ALSO 3 semi-tones. You could also call this chord a minor flat 5. In conventional pop songs you won’t come across this chord often, as it has a very uncomfortable sound and needs to resolve to an adjacent chord to sound nice (more on this in my upcoming jazz chords blog). Here’s a piano demonstration of the VII chord, B diminished:

B – D is 3 semitones (a minor third) and D – F is too. What a mopey chord!

How to work out the complete list of chords for a major key

From the above we can conclude that for any major key the most likely chords will be:

- I – Major

- II – Minor

- III – Minor

- IV – Major

- V – Major

- VI – Minor

- VII – Diminished

This knowledge is extremely helpful if you are working out or writing a diatonic song in a major key (“diatonic” means using the notes from one scale only, with no added sharps or flats).

How to use this to work out a song in a major key:

First work out what key the song is in. You can do this by finding the last chord of the song. This will almost always be the key chord. The key chord will also probably be the most common chord in the song. Bear in mind that the list of chords above only works for songs in major keys and that some songs in major keys add accidentals (extra sharps and flats) in order to add more options. Songs in other keys and modes work in a similar way which will be covered in future blog posts.

Next, apply the key signature to the above rule to work out all the likely chords in that key. Here is an example to work out a song in D major:

- You know that D major contains F# and C# (see circle of fifths above) and thus the chords in the song will most likely be:

- D major, E minor, F# minor, G major, A major, B minor and C# diminished.

- Using Youtube, Spotify etc pause the song every time you hear a new chord. Work out what each one is and write it down.

- To do this, consider whether the chord is major (happy), minor (sad) or diminished (uncomfortable). This will narrow your options down to a choice of three likely chords and you can play through them until you find the right one. Bear in mind that diminished chords are far less common in popular music than major or minor ones.

Youtube demonstration

Depending on your learning preferences you may benefit from a video demonstration. I demonstrate everything in this blog and more in the Youtube clip below. I also show how you can quickly and easily understand and memorise this useful information using my creation, The Amazing Mode Wheel from Finale Guitar! The video is aimed primarily at Celtic Backing Guitarists, but the same theory applies to all conventional Western music.

If you would like a demonstration of this principle and the complete working out songs guide from an experienced and patient teacher then contact me now to book a free trial lesson in Sheffield or via Skype! I will also be releasing more music theory blogs and Youtube clips very very soon so please subscribe to my mailing list on the popup for more blogs and subscribe to my Youtube by clicking here.

Thanks for reading and don’t forget to comment!

If you find my blogs helpful please consider making a small donation through Paypal in order to help fund my web hosting, time etc.