Festival Khetane - Day 2

My trip to Romania 2022 and how we began to work with ACRC to help rehome the Roma of Pata Rât landfill site

Back in August 2022 I was fortunate enough to visit Romania. I’ve been thinking for a long time about the many moral and long term economic implications involved in importing from China and so the aim of my trip was to find an EU manufacturing partner. I was looking for a company who produced quality instruments using responsibly sourced tonewoods, assembled by workers who were paid decently for their labour. I’d heard positive reviews of Romanian instruments and was interested to visit the country so I booked my tickets and set off.

Cluj Napoca

On a sunny August evening I arrived in Cluj-Napoca. As I left the tiny airport and turned towards the city (about forty minutes away on foot), the setting sun was suddenly blotted out by a huge flock of crows, on their way home from a rich afternoon’s pickings on the municipal rubbish tip just outside of town. They massed overhead, forming a great swirling, croaking current which pushed me down the cracked road towards the city. Thankfully the cloud dispersed as I arrived on the outskirts of Cluj, and as I got closer to the bustling metropolitan hub I was greeted by an intriguing mixture of Orthodox architecture, monolithic communist tower blocks and rapidly expanding modern construction sites. Despite its convoluted and often painful history, Cluj is a city bursting with life, especially at night! With a population of around 308,000 of whom around 55% are under 30, I got a real sense that the city aspired to greater things, with new values and customs springing up from a difficult historical base. “Cluj is the future” read the huge billboards (in English) which flanked the main road through the centre of town. As I strolled the bustling streets on my first evening I could well believe it.

On a sunny August evening I arrived in Cluj-Napoca. As I left the tiny airport and turned towards the city (about forty minutes away on foot), the setting sun was suddenly blotted out by a huge flock of crows, on their way home from a rich afternoon’s pickings on the municipal rubbish tip just outside of town. They massed overhead, forming a great swirling, croaking current which pushed me down the cracked road towards the city. Thankfully the cloud dispersed as I arrived on the outskirts of Cluj, and as I got closer to the bustling metropolitan hub I was greeted by an intriguing mixture of Orthodox architecture, monolithic communist tower blocks and rapidly expanding modern construction sites. Despite its convoluted and often painful history, Cluj is a city bursting with life, especially at night! With a population of around 308,000 of whom around 55% are under 30, I got a real sense that the city aspired to greater things, with new values and customs springing up from a difficult historical base. “Cluj is the future” read the huge billboards (in English) which flanked the main road through the centre of town. As I strolled the bustling streets on my first evening I could well believe it.

Hora Instruments

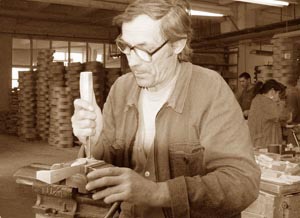

Hora Instruments – lovingly hand made in Romania!

In commercial terms, I certainly found what I was looking for in the form of Hora Instruments. The company was founded in 1951 by the master luthier Roman Boianciuc who built the first violin in Reghin (about 100km east of Cluj). The city is now synonymous with instrument-making, with many other smaller manufacturers springing up around the original Hora factory over the last 70 years. I enjoyed going round the music shops of Cluj, chatting to the people who worked in them and playing the instruments on offer. One thing that I heard from everyone was “When it comes to folk instruments, classical guitars and ukuleles, you really can’t beat Hora”. Producing more than 50.000 guitars, 5,000 mandolins, 10,000 violins and 2,500 cellos and double basses every year and exporting to distributors all over the world they certainly know what they’re doing! I also found that their ukuleles and bouzoukis had a really beautiful tone with a clean, bright top end, lots of punch in the mids and a very pleasing sustain with plenty of warmth. This is thanks to the responsibly sourced local tone woods used. These primarily come from the Carpathian mountains, where spruce and maple grow slowly at altitude. They are then naturally seasoned for 5-10 years giving them a beautifully “opened out” tone. This use of local resources also helps to keep their costs and environmental impact down, as does their use of water based lacquers.

The problems of a post-communist nation

On a commercial level, my trip had been successful and I was enjoying the vibrant nightlife and beautiful surrounding countryside. However, the more time I spent in Cluj, the clearer it became that the city has its problems. Despite achieving some of the highest economic rates of growth of any country in the EU over the last five years, Romania’s economic outlook is still hampered by governmental corruption and lamentably poor infrastructure (the average passenger train for example travels at a regal 40km per hour compared to about 100km/h in the UK). As I understand it this is largely due to a poorly managed switch from communism to capitalism after the revolution of 1989, which allowed institutional corruption to set in right from the outset. Today, following Romania’s entry to the EU in 2007, housing, food and general commodity prices have all risen to levels in line with those paid by most western european citizens. This is despite the fact that the average Romanian earns roughly a quarter of their wage. This has led to a burgeoning housing crisis caused by rapid population expansion and stagnating wages. The public is naturally looking for someone to blame, and unfortunately they have found an easy scapegoat in the country’s Roma community. Shamefully, government (both national and local) has played along with this. In one notable incident in 2010, around 300 roma were forcibly evicted from their homes in Cluj Napoca and escorted to Pata Rât, the toxic landfill site which had greeted my arrival. This took place a week and a half before Christmas. They were by no means the first- estimates from the time suggested that upwards of 1,500 displaced people were already living on and around the Pata Rât site. At time of writing in 2022, the number of men, women and children surviving atop a toxic combination of rotting waste and discarded chemicals is now around 2,000, the culmination of a long campaign of systematically removing Roma settlers from urban areas and dumping them in “temporary rehoming zones”, far from the public gaze, where they languish indefinitely.

On a commercial level, my trip had been successful and I was enjoying the vibrant nightlife and beautiful surrounding countryside. However, the more time I spent in Cluj, the clearer it became that the city has its problems. Despite achieving some of the highest economic rates of growth of any country in the EU over the last five years, Romania’s economic outlook is still hampered by governmental corruption and lamentably poor infrastructure (the average passenger train for example travels at a regal 40km per hour compared to about 100km/h in the UK). As I understand it this is largely due to a poorly managed switch from communism to capitalism after the revolution of 1989, which allowed institutional corruption to set in right from the outset. Today, following Romania’s entry to the EU in 2007, housing, food and general commodity prices have all risen to levels in line with those paid by most western european citizens. This is despite the fact that the average Romanian earns roughly a quarter of their wage. This has led to a burgeoning housing crisis caused by rapid population expansion and stagnating wages. The public is naturally looking for someone to blame, and unfortunately they have found an easy scapegoat in the country’s Roma community. Shamefully, government (both national and local) has played along with this. In one notable incident in 2010, around 300 roma were forcibly evicted from their homes in Cluj Napoca and escorted to Pata Rât, the toxic landfill site which had greeted my arrival. This took place a week and a half before Christmas. They were by no means the first- estimates from the time suggested that upwards of 1,500 displaced people were already living on and around the Pata Rât site. At time of writing in 2022, the number of men, women and children surviving atop a toxic combination of rotting waste and discarded chemicals is now around 2,000, the culmination of a long campaign of systematically removing Roma settlers from urban areas and dumping them in “temporary rehoming zones”, far from the public gaze, where they languish indefinitely.

Khetane Festival and the Roma of Pata Rât

The outskirts of Pata Rât

I first discovered the Pata Rât slum thanks to a tipoff from Retro Hostel’s receptionist when I mentioned I was a music teacher. The Khetane Festival 2022 was the first of its kind, organised entirely by the inhabitants of Pata Rât using a combination of charity and EU funding to bring together Roma communities from around the country and the general public from Romania and beyond. The festival’s aim is probably best stated by its founders; “To be honest and real. Something for us. For us ALL. We want to see each other. We want to do it together. We will have concerts. Debates. Screenings. Fashion shows. Activities for children. Exhibitions. We go to the roots. We do it from scratch. As much as we put in is as much as we will get out. Help us feed our artists. To transport our artists. To set-up the stage. We rely on ourselves. This is about our humanity.”

“Khetane” means “together” in the Roumani language and this event certainly did unite a huge range of visitors. I arrived by bicycle via the small road that weaves through the lightly grassed-over mountains of refuse, glancing with some trepidation at the dogs that guarded certain sections along the way. My anxiety was soon alayed though as I bumped into a Romanian student (who spoke flawless English), who was cycling to meet some friends at the festival. As we arrived at the village of shacks (one of the four main shanty towns of Pata Rât) we were greeted by the sounds of Roma EDM, blaring from a soundsystem with a packed out dancefloor in a tent in front of it (unfortunately I’d missed the first day of the event which showcased live performers). Teams of volunteers handed out chocolate croissants to grinning, muddy children. Huge numbers of Roma, visitors from the city and guests from further afield danced or looked on admiringly at the acrobatics on display. Off to one side an information table had been set up by a local NGO offering free books on the housing woes inflicted on the Roma (I am still working on my Romanian so unfortunately can’t share any passages). Behind us a huge cinema screen was being erected on a metal frame for a documentary screening in the evening. Groups of children ran between the legs of visitors and staged pitched battles with the bags of straw that had been used as seating earlier in the day. At the perimetres groups of police towered menacingly over their heads, rifles in hand.

“Khetane” means “together” in the Roumani language and this event certainly did unite a huge range of visitors. I arrived by bicycle via the small road that weaves through the lightly grassed-over mountains of refuse, glancing with some trepidation at the dogs that guarded certain sections along the way. My anxiety was soon alayed though as I bumped into a Romanian student (who spoke flawless English), who was cycling to meet some friends at the festival. As we arrived at the village of shacks (one of the four main shanty towns of Pata Rât) we were greeted by the sounds of Roma EDM, blaring from a soundsystem with a packed out dancefloor in a tent in front of it (unfortunately I’d missed the first day of the event which showcased live performers). Teams of volunteers handed out chocolate croissants to grinning, muddy children. Huge numbers of Roma, visitors from the city and guests from further afield danced or looked on admiringly at the acrobatics on display. Off to one side an information table had been set up by a local NGO offering free books on the housing woes inflicted on the Roma (I am still working on my Romanian so unfortunately can’t share any passages). Behind us a huge cinema screen was being erected on a metal frame for a documentary screening in the evening. Groups of children ran between the legs of visitors and staged pitched battles with the bags of straw that had been used as seating earlier in the day. At the perimetres groups of police towered menacingly over their heads, rifles in hand.

Alex the social worker (left) and other visitors attending a talk at the festival

“They won’t do anything with the media here” I was told by local NGO social worker Alex who kindly made time to explain a little of the history of Pata Rât to me. “It’s when the tourists go home that we’ll see what the police do next”. The police do not have a positive reputation in Pata Rât. Aside from helping to eject many Roma from their homes, they have also been known to confiscate identity papers which are never returned to their owners, leaving them unable to work, obtain health care etc. That’s to say nothing of the everyday stories of police brutality, with beatings a regular feature of life on the site. It’s hard for western Europeans, and many Romanians, to believe that an EU member state in this day and age could possibly be forcing around 2,000 people to live on a dangerous, toxic landfill site on the outskirts of its largest city but in reality this is a continuation of over 1,000 years of oppression of a little understood ethnic minority.

Roma history

The Roma first arrived in Europe from northern India between the eighth to tenth centuries. They traveled widely, offering various services most notably metalwork, music and dance. It would be hard to name any other group who have been so poorly treated in European history, with so little recognition paid to their past in modern times. In 2021 they were added to the British census for the first time ever, even though some 200,000 Roma live here. Despite their forming a significant minority population in most European countries, it took until 1976 for their existence as an ethnic group to be recognised at all.

A potted history of the Pata Rât site, on the wall in front of the local church (built from recycled material)

The Roma’s history in Romania has been deeply unpleasant from start to finish. From their arrival in the region in the late 1300s (following a period of migration within the Byzantine empire), they were swiftly enslaved and forced to work the land by local fiefs. This state of slavery persisted for the best part of 600 years right up until the mid 1800s. During the process of emancipation, the ruling Habsburg dynasty enacted a raft of measures designed to force the Roma to assimilate, which included outlawing the Roumani language, preventing them from dealing horses, a complete cessation of nomadism and even banning marriage between Roma couples. Those Roma unfortunate enough to still be slaves in the early 1800s were cruelly exploited in the service of the industrial revolution, with teams of slave workers being bought and sold at huge markets and hired wholesale by their owners, as unwaged labour teams for agriculture and construction. From 1860-1914 the Roma enjoyed a period of being merely the most poorly paid and socially marginalised group in the country- a slight improvement on 600 years of slavery. Many of them followed industrial jobs into the cities and many more emigrated throughout Europe, Scandinavia and the Americas. The interwar period saw the decline in nomadism for the Roma due to a combination of lack of demand for their services thanks to industrialisation and prevention of traveling by local police forces.That being said, between 1918 and 1938 the Roma enjoyed a period of improvement in their lot with Roma cultural organisations appearing and flourishing. Unfortunately that was all to change. Throughout the 30’s eugenics reared its ugly head and in 1940 Ion Antonescu was appointed dictator by the Nazis. From 1940-1945 he deported some 50,000 Roma to Transnistria. Around half of them died. In total, almost a quarter of the total Roma population of western europe (some 500,000) were murdered by the Nazis during World War II.

After the communist regime’s arrival in 1945, things improved a little with initial attempts to provide state housing for the Roma being fairly successful. However, over time the state’s desire for enforced assimilation led to segregation in housing and employment, repression of the Roumani language, confiscation of Roma property including horses and wagons and even child abduction and forced sterilization. From the fall of communism in 1989 things really haven’t improved. There is still widespread racism against the Roma, and this is deeply embedded in the machinery of government, so much so that rather than attempting to change attitudes and enhance housing provision, those in power prefer to hide the problem by forcing a marginalised community to live in conditions which are tantamount to slow murder. This is the reality of Pata Rât. According to the European Public Health Alliance, “on average, Roma will die ten – fifteen years earlier than most Europeans. Roma are less likely to be vaccinated, have fewer opportunities for good nutrition, and experience higher rates of illness. In some countries, six times as many Roma infants do not make it to childhood. If they do, they will have experienced more infections and diseases than other groups living in similar economic conditions”. As for Roma living on landfill sites… You need only look at the second episode of Channel 4’s The Romanians Are Coming to hear directly from local resident Alex Fechete, showing a film crew around the houses on the Pata Rât site. “Here by this fence is where they drop all the chemicals. Everything that’s bad, that sucks, that’s poisonous- they come and store it underground. The first year I got a stomach disease from this kind of sh**… And now? I’m immune! I can go on the moon, I can breathe on Mars. It’s no problem for me!”.

Alex Fechete and the work of ACRC

Local hero Alex Fechete enjoying the music at Khetane Festival

I was lucky enough to meet Alex at the Khetane festival. Like most of the site’s residents, his first language is Romanian, his second Roumani. He also speaks English fluently. When I asked him how he learnt he laughed and told me; “Cartoon Network!”. Alex is a funny guy, inspiring and charismatic with an unbelievable amount of patience (especially for ill-informed English visitors who own guitar shops!) and the stoic sense of humour needed to get up every day and fight an ongoing battle in the face of overwhelming public stigma and barbaric mistreatment. I spoke at length with him, the other Alex- the social worker I mentioned earlier- and Aaron Roberts, an English ex-pat, photographer and founder of English language local news site ClujXYZ.com, who told me about local life and kindly provided the photographs on this page. The fact that the festival, the first of its kind, took place at all is incredibly encouraging and the good news coming from all three of them is that there is hope for the residents of Pata Rât. The public both in Romania and internationally are starting to take notice- the main thing that’s missing is the funds to make events like Khetane happen and the much needed investment required to keep the children of Pata Rât going to school and mixing with the rest of Romanian society.

That’s why I’ve partnered with ACRC, which translates to the “Coastei Roma Community Association”. In their own words they are; “a grassroots organization formed after the evacuation of 350 Roma people from Coastei street in Cluj-Napoca in December 2020. The association is part of the project ‘The violation of the right to live in a healthy environment and the struggle of the Roma from Pata Rât for housing justice’”. For every Hora instrument sold through Finale Guitar we will be donating £5 to the amazing work of this charity. They primarily work with the children of Pata Rât, providing cultural and educational activities. They also organise public events and exhibitions to raise awareness of the plight of the people of Pata Rât and demand action. Currently they are raising funds for a project to provide instruments and music lessons and keep the proud Roma musical tradition alive for the next generation. This will give the children of Pata Rât a sense of pride and purpose and a skill which they can use to get out into society, raising awareness and much needed income. In short your purchase will not only net you an amazing instrument, but will also help us to support this powerful and sorely needed work. You can also add a further donation using the links on the listings for all our Hora Instruments or by clicking here.

Acknowledgements

There are many people I’d like to thank from my time in Romania. Both the Alexs are truly inspirational people persevering against unbelievable odds and I thank them both for taking the time to discuss the situation with me. Aaron Roberts was a pleasure to talk to and has provided beautiful photos from a really incredible event which deserves to be as widely documented as possible. All the staff at Hostel Retro were great, especially the cleaning ladies who put up with my rubbish Romanian! I was also extremely surprised by Marius from Hora Instruments who has kindly agreed to help me raise money for the ACRC. Given the huge public stigma against the Roma in his home market I never thought he would take a punt on this project and I am extremely grateful to him and everyone at Hora for working with me to raise funds for this vital cause (not to mention for making such lovely instruments). Most of all I’d like to thank the people of Pata Rât for sharing their unique culture with me and making me so welcome. Keep fighting.

The children of Pata Rât

I donate the last paragraph of this post to the kids of Pata Rât. No child should be forced to live on a mountain of litter. As I watched the dancers, a little boy of about six ran up and hugged me. Then he tilted his little curly head to look up at me and grinned. He was missing two teeth. I smiled back and he ran off to rejoin the hay fight that was taking place on the other side of the marquee. I will never forget this. Without the work of people like the Alexs and ACRC children like these, through no fault of their own other than being born in the wrong place, are destined to endure life on a poisoned strip of land unfit for cockroaches, let alone people. As they try and work their way out of Pata Rât they face the grinding away of their innocence by a life of mistrust, social ostracism, poverty and illness. This needs to change.

I will certainly be doing whatever I can to help ACRC. I hope you will too.

Donate

We donate £5 for every Hora instrument sold to ACRC. You can also make a donation directly by Paypal or card payment by clicking here.

Further links:

History of the Roma in Eastern Europe

Small Steps- another charity working with the inhabitants of Pata Rât

1 Comment

Thank you for sharing this Nye.