Chord construction explained- 7, 9, 11, 13, major, minor, dominant etc

I am often asked questions like “what’s the difference between a major and a dominant 7 chord” or “why is this an add 9 chord not a 9 chord”. When you first discover the vast selection of chords with numbers in, it can seem like a giant, scary music theory melange… In this blog I am going to be explaining how chords are named and hopefully demystifying this confusing subject for beginner guitarists!

Major, minor and dominant triads

Let’s start at the beginning. There are three main families of chords. These are called “major”, “minor” and “dominant”.

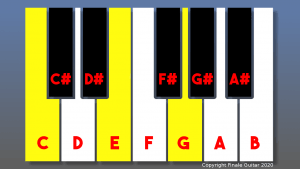

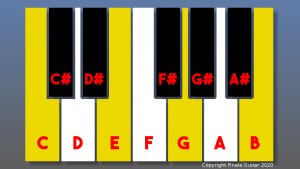

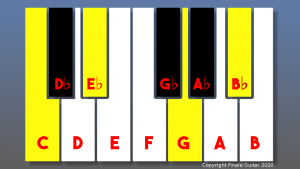

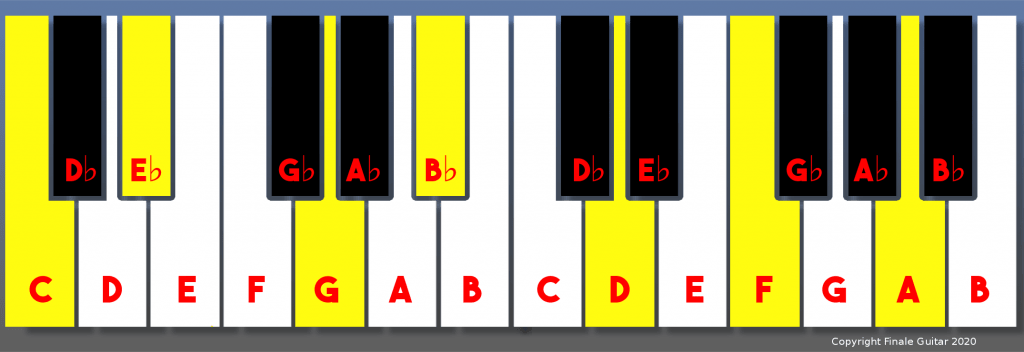

The simplest type of chord is called a “triad” aka three notes stacked up on top of each other. These will be notes 1, 3 and 5 of the relevant scale so to make a major triad you take notes 1, 3 and 5 of the major scale and stack them up together. For example if we want to make a C major chord we go through the scale of c major (no sharps or flats) and pick out the first, third and fifth notes that we get to aka C, E and G. I have demonstrated chord constructions on a piano for this blog as it’s a lot easier to visualise notes on a piano than a guitar because the sharps and flats are thoughtfully coloured in.

C major triad

No matter what order you stack the notes in they will still make a C major chord, even if the root note (aka C) is not at the bottom of the chord. We call this “inverting the chord” so if you hear someone say a chord is “first inversion” they mean the third note or the scale is being played as the lowest pitch in the chord and second inversion is the fifth note being used as the lowest pitch in the chord. Inverted chords are commonly written like fractions. The numerator tells you which chord should be played and the denominator tells you which of its notes should be in the lowest pitch. For example, G/B would be the notes of a G major chord (aka G, B and D) piled up with the B at the lowest pitch within the chord. When talking about this chord you could call it either “G over B” or “G in the first inversion”.

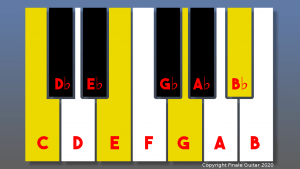

To construct a minor chord we do the same thing but with a minor scale instead. So for a C minor chord we would take the first, third and fifth notes of a C minor scale and stack them up. Again the order of the notes isn’t really important so long as they are all there. Notice that the only difference between a major and minor triad is that the third note is flattened by a semi-tone.

C minor triad

In the simplest terms, major chords are “happy” and minor chords are “sad”. I once asked a psychologist who’d just begun to play the guitar what the difference in sound between two chords was. After I’d played her a major and a minor chord, she told me that “the first sounded meaningless but the minor one has gravitas”. However you remember them, there is a very clear difference in sound between the two main chord types.

Tetrads, or four note chords

Major 7 chords

A major seven chord is the same as a major chord except that as well as notes 1, 3 and 5 from the major scale we also add the 7th note. This gives the chord a wistful quality. Here is an example of a C major 7 chord:

C major 7

Again you can stack the notes in any order of your choosing but it is conventional to have the root (C) at the bottom pitch.

On the subject of inversions, your ears will infer from the notes present in a chord what the root note is, even if it is not at the bottom of the chord and even if it is not present at all! I will be going into the fascinating physics and neurological mechanisms involved in this process in future blogs.

Minor 7 chords

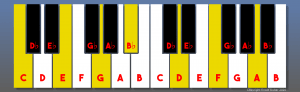

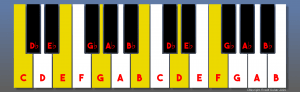

A minor 7 chord works in a similar way to the major 7 chord, except that the 3rd and 7th notes are flattened. For a C minor 7 chord for example, the 3rd, E, becomes E♭ and the 7th, B, becomes B♭ as shown below.

C minor 7

Dominant 7 chords

Next we have dominant 7 chords. These have an uncomfortable feeling which needs to be resolved by following them with certain chords. In this way they can lead a chord progression in a certain direction or even be used to modulate to another key.

The dominant chords are the family denoted by letters and numbers, eg C7, D9, E11 etc. To make a dominant chord you go through the major scale but with the 7th note flattened (which is effectively a mixolydian modal scale, as discussed in my blog on the modes here and in this youtube clip). Take the 1st, 3rd, 5th and 7th notes and stack them up in your preferred order. For C major, for example, we would flatten the seventh note, B, to B♭. People with older browsers may not be able to see the flat symbols in this section, so just to confirm the last bit of the last sentence was “B to B flat” and I will be referring to B flat for the rest of this paragraph! Then we would stack up C, E, G and B♭ to get a C7 chord. While you could call the chord C dominant 7, most people don’t as it’s easier just to say C7. If a chord with a number doesn’t specify major or minor then it’s a dominant chord.

C (dominant) 7

Dominant chords “want” to resolve down a fifth (this is because of the intervals contained within them, but I won’t go into it here). They are usually used as chord V in a major key because they want to resolve down a fifth and chord V back to chord I is the “perfect cadence”, which we recognise as marking the end of a musical phrase or section. They can also be used in other ways, for example as all three chords in a standard blues progression or at any point in a jazz tune where the following chord will be down a fifth from the current one.

For example our C7 chord could be used as chord V in the key of F major.

Chords with other extensions (numbers)

So what about the other number chords? Firstly, the chord’s name will tell you what kind of seven and third are included. A “major family” chord will always have a major 3rd and major 7th. A “minor family chord” will have a flattened 3rd and flattened 7th (as in the dorian mode). A “dominant family” chord (aka a chord like C9 with no “major” or “minor” in its name) will have a major third and flattened 7th (as in the mixolydian mode). This is always true no matter what extra numbers are present. For example, C major 9 has C, E♮ (major 3rd), G (5th) and B♮ (major 7th) as its base notes with extras added on top. C minor 9 has C, E♭ (flattened 3rd), G and B♭ (flattened 7th) + extra notes. C9 (recall that this is from the dominant family as it doesn’t specify major or minor) has C, E♮ (major 3rd), G (5th) and B♭ (flattened 7th) + extras.

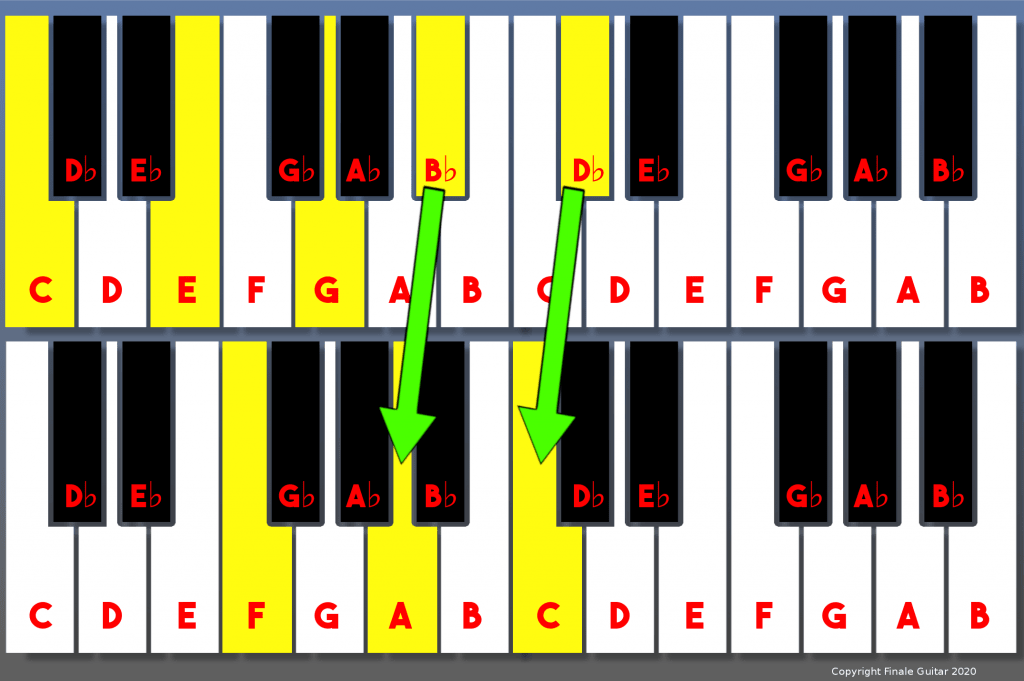

So what are the extra notes? Let’s look at C9 as an example. This is the same as the C7 chord except with another extra note added, which will be the 9th note of the C major scale. Now obviously a scale only has 7 notes with the 8th being the root again. The “9th” note is thus another way of referring to the “2nd”. The reason for this confusing naming convention is that adjacent notes on the keyboard do not sound good together, so the 2nd note (in this case D) is played an octave higher in order to avoid clashes.

Therefore a 9 chord contains notes 1, 3, 5, ♭7 and 9 otherwise known as 2.

C9 chord

An 11 chord works exactly the same way except that you also add the 11th note (same as the 4th note) and…..

C11 chord

A 13 chord works exactly the same except with the 13th (or 6th) note added as well.

C13 chord

Practical considerations- which notes to leave out

Practical considerations- which notes to leave out

You may now be thinking “how is it possible to play a 13 chord which contains the notes 1,3,5, ♭7, 9, 11 and 13 when I have only four available fingers and six strings”. The good news is that you can leave out most of the notes. The notes of a chord can be omitted in this order:

- Leave out the 5th as nobody likes it and it smells. Just kidding, the 5th note is only really there to back up the root, but it doesn’t really add any emotional content to your chord- it’s just a muscle note to pad the chord out so get rid of it for complex chords.

- Next get rid of the root because the other notes all have jobs- the third note is important as it tells you whether the chord is happy or sad, the extra tones (7, 11, 13 etc) add flavour but the root is only really a guide to give the ears a handle on the function of the chord. If you’re playing jazz (which you probably are if you’re delving into all these weird chords) then you will mostly likely have a bass instrument playing the root anyway. The root is also implied so doesn’t actually need to be there- thanks to the science of undertones, your ears will naturally infer what the root is from the chord’s other notes.

- If you are playing a 13 chord and are not playing with a bassist, organ, accordion or other bass-filling instrument then you might want the root to be present. However you do not really need the 9 or the 11 so you would be best off playing 1,3, ♭7, 13 and adding any other notes from the selection (eg 5, 9 or 11) to taste.

Major family

Next we have major 7, 9 and 11 chords which work in exactly the same way except that the 7th note is NOT flattened. In other words you use the normal 7th note of the major scale. Therefore a C major 11 chord (for example) contains C, E, G, B, D and F aka 1, 3, 5, (major)7, 9 and 11. As you have only so many strings and fingers, the 5 can go, the 9 is optional and the root is next in line for omission.

C major 11 chord

Minor family

Minor 7, 9 and 11 chords work on a similar principle. They always have a minor third and flattened seventh, but the other added notes are as they would be in the major scale (those of you familiar with modes could see these as being built from the notes of the dorian mode). Therefore a C minor 13 contains C, E♭ , G, B♭, D, F and A as on the diagram below:

C minor 13 chord

Altered dominants

Altered dominant chords are the other type of snazzy chord available to you. These are constructed the same as other dominant chords except that one of the numbered notes will be raised or lowered by a semi-tone. For example a C7♭9 chord would contain C, E, G, B♭ and D♭- it’s like a C9 chord but the 9th note, D, has been flattened by a semitone.

C7 flat 9 chord

These chords are a great way to create extra tension in a progression. This is then usually resolved by following up with the chord whose root is a fifth below, eg C7♭9 would resolve to F. This would commonly be used as a final chord progression (or cadence) in a song in the key of F major as we will see in the next section.

Altered dominant chords for perfect cadences (V-I)

In the key of F major, C is chord V. A song’s final cadence is most likely to be V-I (the progression traditionally used to let the listener know a section is finished). Using an altered dominant in place of chord V makes the progression sound “extra finished”.

This works because the altered note, in this case the flat 9th of the C chord, D♭, is not from the F major scale (which contains F, G, A, B♭, C, D and E). This creates a deliberate clash, but it is “resolved” by descending a semitone to the C note in the following chord. This C is the fifth from the F major chord, a note which is very comfortably in the key of F major.

C7b9 to F major – C’s uncomfortable flattened 9th (Db) descends to C, the 5th of F major.

“Add” chords

If you hear an add chord mentioned it simply means the ordinary chord with one extra note added, so C add 9 is a C major chord with a D added to it (AKA C, E, G, D) etc.

C add 9 chord

“Sus” or suspended chords

These come in 2 flavours, “sus 2” and “sus 4”. In each the third note of a chord has been replaced by one of it’s adjacent neighbours, giving the chord an unresolved feeling. These are usually played after chord V and then followed with the regular chord for an extra finished sounding ending.

C sus 2 chord

C sus 4 chord

NB Playing sus 4, then sus 2, then the regular chord is a classic way to end a song / piece.

The end

If you would like to learn more about how to use all the chords above, check out my blog on harmonising the major scale and Greek modes or read up further on the intervals within chords and jazz arpeggios.

Don’t forget you can book a free first lesson today in person in my studio in Sheffield or via Skype, Zoom or Whatsapp.

Finally if you want to learn LOADS of crazy jazz chord voicings and lots of very artistic contexts in which they can be applied then check out one of my absolute favorite books, Chord Chemistry by the amazing Ted Greene.

Buy it here: